During the last six years, I have been forced to confront the collapsing health of my family. Not by coincidence, my reflections on these changes and death itself led me to writers like Viktor Frankl and branches of thinking such as Existentialism and the Greek and Roman school of philosophy known as Stoicism.

During the last six years, I have been forced to confront the collapsing health of my family. Not by coincidence, my reflections on these changes and death itself led me to writers like Viktor Frankl and branches of thinking such as Existentialism and the Greek and Roman school of philosophy known as Stoicism.

The Stoic philosophers from ancient Greece and Rome provide a roadmap that remains remarkably relevant today. The most famous ancient stoics—Epictetus, Seneca, Marcus Aurelius—did not focus on abstractions. Rather, they wrote about the most pressing realities of life and issues of what define us and how we live each day.

At this point in my own life’s journey, I found comfort in old ideas that embraced questions about death. As Seneca wrote, “A man cannot live well if he knows not how to die well.” Stoic ideas helped me think about how all of us can prepare ourselves for misfortune and navigate through the worst possible events, in order to confront what inevitably lies ahead.

My journey, with my family, was now one confronting inevitable loss. This chapter of my life story, with my family, will perhaps soon end in the death of the remaining two members of my nuclear family—my mother and sister.

Losing my Mom

My father died in 1985, when I was 20, and I can scarcely remember him as a person. He was an alcoholic and unimportant in my life. I unfortunately lost my mother more than six years ago, but this loss is ongoing.

My father died in 1985, when I was 20, and I can scarcely remember him as a person. He was an alcoholic and unimportant in my life. I unfortunately lost my mother more than six years ago, but this loss is ongoing.

In 2013, she was diagnosed with early onset Alzheimer’s disease. The illness has been especially cruel to her husband, my stepfather, who saw his intimate partner and best friend of 30 years slowly lose her mental abilities and her ability to function as an independent adult. I have observed her slow decay, mostly during short visits and on phone calls that always got worse with each week, month, and then year.

My mother changed from being someone with a razor-sharp mind and who loved crosswords to a woman who could no longer remember the names or even faces of her neighbors and family.

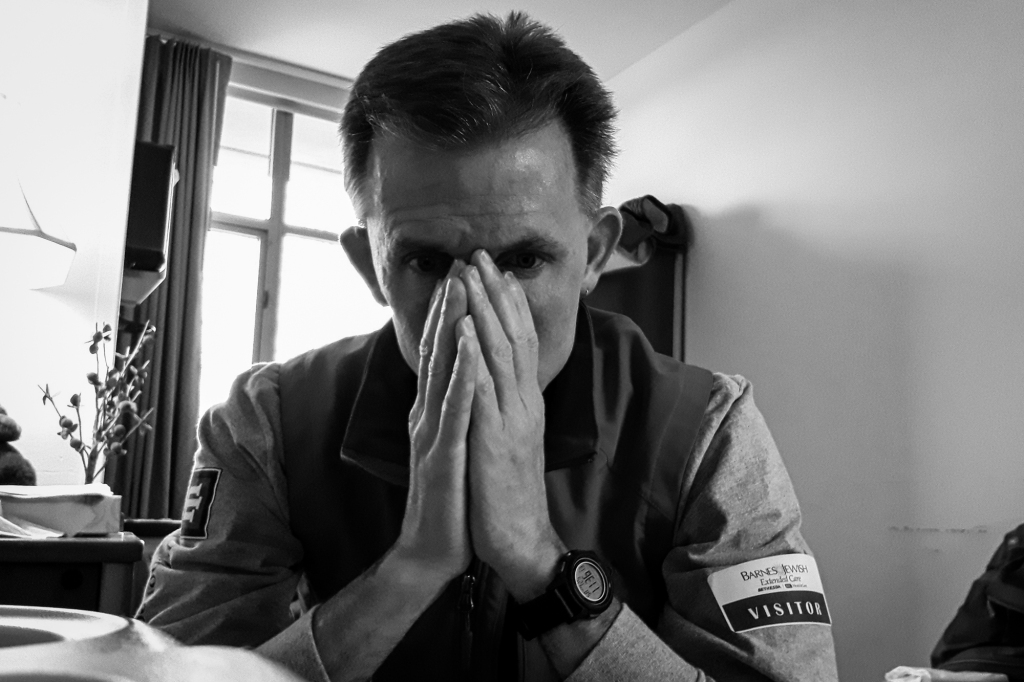

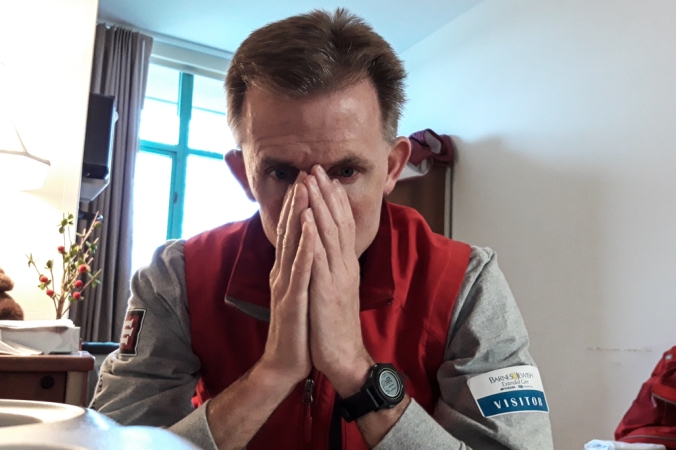

On this last trip to St. Louis in September 2019, we were alone. I asked her, “Who am I?” She gave me a long look with that blank stare, created by the destruction of her neurons and the accumulation of amyloid plaques in her brain. She replied with my stepfather’s name. I said, “No, mom, it’s your son, Rudy.” She didn’t reply. She then asked me a question she had asked half a dozen times earlier in the last 15 minutes.

I have spent these last six years flying back and forth from Seattle and then Portland to her home in the St. Louis area. My trips were motivated by personal concern for her and her husband caregiver and a sense of duty to help as her son.

I have shed tears. I have felt anguish. I have gnashed my teeth. I have cursed scores of times to myself as I walked alone after work, daylight or dark. I have felt powerless. I have felt my desires for my own dreams bend and be extinguished, just so I could be there for her, albeit from afar.

When I read about my friends’ lives, involving travel or a life where the future is filled with promise, I compare it to my stepdad’s world. His involves non-stop and constant care for my mom.

I have, in the end, simply abandoned thoughts of vacation and time alone that don’t involve flying halfway across the continent, so I can spend time with her. On past trips we have held hands and took walks. We could even squeeze in visits to the St. Louis Art Museum and Missouri Botanical Garden. Even those stopped on my last trip.

On this trip, like the ones before, she asked me questions she had asked dozens of times before: Where do you live? Why do you live n Portland? Why won’t you live here? Do you have a girlfriend?

My mom often chastised me, saying, that’s too far away, you should be closer, even when she has no idea who I am or that she even had a son.

Losing my Sister

During these last six years, and for at least a decade earlier, I have also watched my sister slowly spiral out of control.

During these last six years, and for at least a decade earlier, I have also watched my sister slowly spiral out of control.

She has battled addiction, obesity, mental health issues, a long spell of homelessness, and finally the collapse of her body. Her obesity finally made it nearly impossible for her to walk. After living on the mean streets of St. Louis for months, and then in an unsanitary drug house in a very unsafe St. Louis neighborhood, she rebounded with the help of my mom and stepdad. My sister found a low-paying but stable job with Missouri’s welfare office.

Yet each visit, from 2000 on, turned into a portrait in loss. By the last time I saw her in January 2019, just before she had a heart-attack, she was out of her job, living in squalid conditions alone, and having no contact with anyone or any person except a former drug addict neighbor in a poor south St. Louis suburb.

Each time I came, her apartment looked dirtier and more cluttered and chaotic. I am choosing not to share the details. They are too depressing and also private.

Finally, in July 2019, she called for first responders who discovered her collapsed on her apartment floor, unable to walk. She had deep and open pressure ulcers and was immediately taken the emergency room at Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis. From there the hospital managers and social workers placed her in skilled nursing facility in the city that accepted Medicaid eligible patients. She moved into the facility that month and has been bedbound and no longer able to walk.

Her new home is a facility for indigent patients, all eligible for Medicaid-paid care. The population is a mix of mostly older African Americans and fewer whites. When I visited in September 2019, more than half appeared bedbound. Patients with mental illnesses wandered the halls, without interference from staff. The front door was coded, and no one but staff could get out without the punch key.

To me, it felt like a madhouse from the Victorian era, with staff unconcerned with the patient wards in their care or visitors from the streets who could walk in the facility without even signing in.

No staff member required me to present my ID or sign in. So I could wander the facility without interference, startled that no one cared who I was. In one of the community rooms, I saw silent, elderly, and sick patients gaze blankly at their television. Others sat in the courtyard, silent and hunched over. Still others in their rooms lay silent, with their televisions blaring reality shows and their faces staring blankly at the blue light. I imagined this was like hundreds of others similar facilities nationwide.

My sister looked like she had aged 10 years. She had lost one of her front top teeth. She had a bad rash and dirty, unkempt hair. She remained unable to walk.

The hardest part of my trip was visiting my sister’s cluttered, dirty apartment that had long gone to hell. Amid the clutter that littered each room, I found evidence of her past life. I located her diaries she had kept from the time she was in her 20s, still with dreams of living a good life, even as it was slowly going sideways from her substance-abuse problems. I found her jewelry she made as a hobby for years, as her mobility began to decline and her world closed in on her.

I spent about two hours finding all of her legal documents and her writings. That was my plan from the start. I put those in a pink plastic tub and filled another with her nicest dresses, pants, and shirts, even though I knew she likely would never wear them again.

We had a falling out when I refused to help her rent a storage locker to put her stuff. She cried, feeling betrayed. I knew from all I had seen she would not leave this place or another. She still believed she could walk again and live on her own with her public assistance.

On my last morning in St. Louis, I visited her room again. Her roommate, who is in her 30s and likely had a mental health disorder, was there. I held my sister’s hand and said I was happy I had come to see her. She looked at me, and said, “I love you.” I responded the way I always had in the past, with a smile.

I then left her room and found one of the young, African-American nurses dressed in purple scrubs. She smiled, punched the code, and the door opened. I walked out into the fresh-smelling fall morning and the sunshine on a beautiful St. Louis day. It was time to catch my flight and leave behind this warehouse for the infirmed.