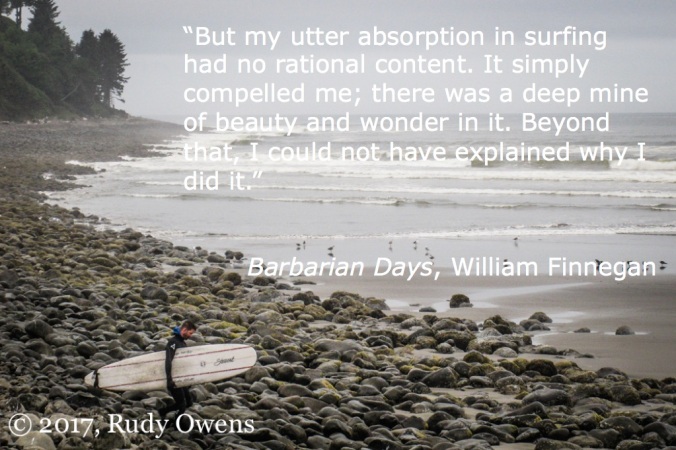

One of who I call the Seaside A-Team catches a tough wave at Seaside, Oregon on a relatively calm day at he Oregon Coast in late September 2017.

A year ago last weekend, I became an Oregon surfer. I now feel confident enough to be in the lineup with every other surfer who shares my passion.

It is a feeling of accomplishment. I started from nothing and had to “wipe out” my way to my new-found status literally hundreds of times. Yes, I had to fail repeatedly before I became competent to feel welcome in the ocean and among the community of surfers globally. I admit I am still slow and clumsy getting upright. I will never be great.

Beginning Surfing Later in Life

In September 2016, I bought a beginner board, the right wet suit, and other gear, and I began the long journey of mastering the art and sport of surfing by travelling from Portland to nearly all surfing spots on the Oregon Coast and even California and Washington.

The journey far exceeded all of my expectations.

The journey far exceeded all of my expectations.

I learned how to understand surf forecasting and paid close attention to the storm systems in the Pacific Ocean that control the weather from Alaska all the way down to the tip of Tierra del Fuego. I met people who shared my passion for the ocean and this highly alluring sport. Many of them have lived and surfed all over the world and country, and we all speak the language of surfing. Some are visitors, and others are residents who now call Oregon home. We all come together in the water, waiting for the wave, patiently sitting on our boards and scanning out for the next set rolling in.

I have learned how to read waves and practice the craft of positioning myself at the right place at the right time. In Oregon’s tough, stormy waters, this involves punching through feisty breaks that pound you as you try to reach to lineup in the water, where the waves give you that window of opportunity to tap their energy and capture moments of transcendence.

I have surfed during snowfalls and blinding rainstorms.

I have seen sea otters, harbor seals, humpback whales, and signs warning me of great white sharks that are common in these waters.

I have made new friends who love to wake up at crazy morning hours and meet at the ocean, just to capture the magic of the ocean in the morning, as the smell of saltwater fills your nostrils and the sound of the wares creates a feeling of calm in morning’s first light.

I have also learned how to ride waves during this time. When I started, I could barely get any. Now, when I go out, I can catch sometimes 20 or 30 rides, if the conditions are perfect or near perfect. Even on bad days, I am mastering the art of riding our very common cheeky waves. These can be fun.

It Was Worth It

This past weekend, on Sept. 22, 2017, I rode perhaps one of the best waves of my life. I started in the lineup at Seaside, near the rocky shore, and grabbed a quiet overhead that took me almost 100 yards to the beach, riding its face and seeing the translucent water carry me on a pulse of energy. My grin grew wider with every second I was steering my nine-foot Stewart longboard. This ride repeated a nearly identical ride I had a week earlier, at the exact same spot.

Now, a year into this journey, I capture each outing with a surf diary, describing the ocean color and smells, currents, sets, wave patterns, colorful characters, my memorable experiences with wildlife and aquatic life, and my memories of the day. As a lifelong writer and journal writer, I can say this is perhaps the funnest journal I have ever kept.

(Author’s note: An earlier version of this essay was first published on Sept. 17, 2017, on my photo blog called What Beautiful Light.)