It has been more than 35 years since my adoptive father died of health complications that followed years of destructive behavior and a losing battle with alcoholism.

Though he has long been buried in a cemetery plot in the Cleveland suburb of Rocky River, Ohio, next to his father and mother, his impact on my life and my family lived on long after he passed away.

Even today, I frequently am forced to confront my long-buried memories of this often violent yet aextremely intelligent man who was an ordained Lutheran minister.

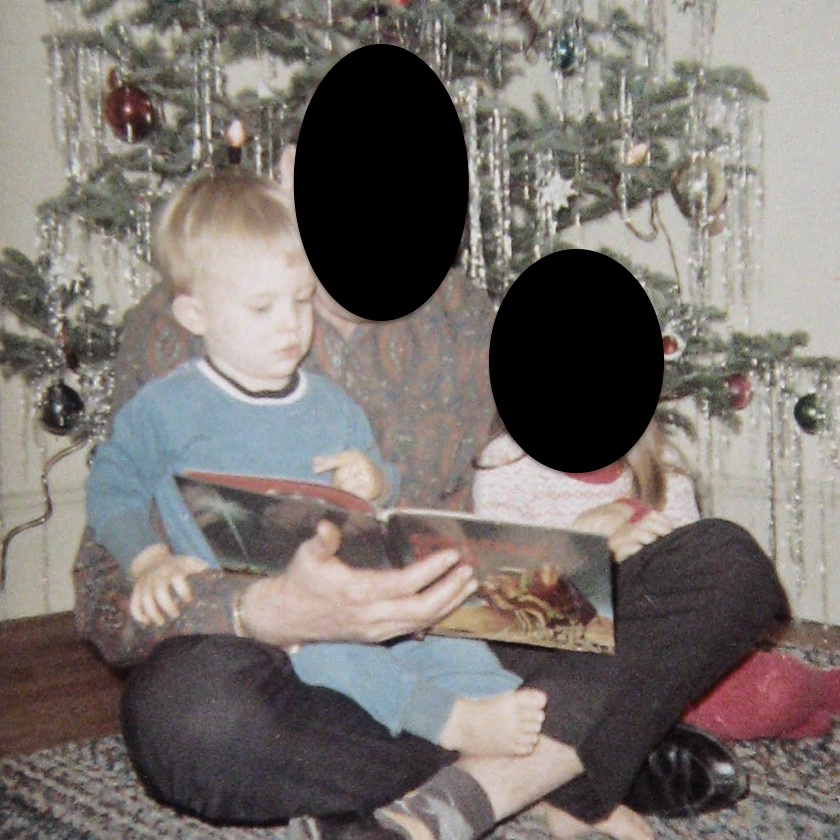

A shot taken with my adoptive father and sister in our home.

For the last seven years, when my adoptive mom was on her long and difficult journey with Alzheimer’s disease, my adoptive father’s memory frequently came up in our conversations. When I visited her in her home in University City, Missouri, flying out from my home cities of Seattle and then Portland, we spent endless hours talking about the past and her memories that grew dimmer over time. She could recall snippets of her past life and share them with me. She frequently repeated ideas or hazy recollections. She repeated two things more than any other during these seven years.

First, she told me, I have the greatest husband in the whole world. She was referencing her current husband and full-time caregiver, my stepfather, who cared for right up until her final day. Second, she told me, my first husband used to beat me. That was a reference to my adoptive father and her first husband, from the summer of 1958 through their divorce in the summer of 1973. During that time they lived in Detroit, moved briefly to Boston in late 1965 and 1966, and then moved to the metro St. Louis area, where my mom lived out the rest of her life.

My adoptive parents in front of their west Detroit home, likely in the late 1950s or early 1960s.

When my mom’s memory was sharper in the early years of her Alzheimer’s, she repeated constantly how often my adoptive father would hit her. She said the doctors told her the violence could have contributed to her awful and prolonged brain-wasting disease. I can still remember those incidents as if they happened hours ago. I too can never forget them.

I would always reply during these countless recollections that, yes, mom, your husband—my stepfather—was the best husband in the world. I would say nothing about her comments on her years of domestic abuse at the hands of my adoptive father—her former husband. These conversations continued until the second-to-last time I saw her alive, in September 2019.

In the end, my adoptive mom had two distinct memories, one of violence and one of love, which she likely had little control over because of her deteriorated state from Alzheimer’s.

Making Sense of my Adoptive Father

Though my life with my adoptive father in a nuclear family lasted eight years, I spent another five more visiting him, first in the St. Louis area and then in the Huntington, West Virginia and Chesapeake, Ohio metro area, where he resettled after the divorce.

Those trips with my adoptive sister to stay with him several times a year, as part of the divorce custodial settlement, were as bad if not worse than the times when we lived as a family under one roof.

I tried to reconstruct those years from memory starting about five years ago, as I began to write my memoir as an adoptee. I remember the day I wrote out the first outline to my memoir on a hot July day on a river beach. I then started with a chapter exploring my childhood and younger years with my adoptive father.

I wrote that chapter first. It proved to the hardest one to do because I had to dredge up memories that were neatly buried.

I also needed to revisit the places of my childhood and youth, in Huntington and Chesapeake, letting me remember things I had forgotten, perhaps as a way to carry on with life. I took a road trip there in September 2015.

My adoptive father lived for several years in this house, owned by the next door Lutheran church, where her served as a minister in the 1970s.

I published an essay on that trip on one of my blogs. I wrote about my childhood trips to see him: “I had no choice in the matter. I had to go there. I had to visit my father. It was bad to awful, and sometimes downright terrible. But when you are young, you are flexible and stronger than you think. You actually can do impossible things, and still come out at the end of the tunnel with a smile. I did. Despite the odds, I really did.”

When I finished the revised text to my memoir in late 2017, I left my first chapter on my adoptive father out. That decision came easily. I decided it was too personal about a relation that shaped my life. No one else would understand that journey but me. By that time in my life, into my fifth decade, I also realized I had become more like the generations who preceded me, who were reserved, not someone who wanted to “tell all.”

I also had come to a deeper realization about living life and finding meaning. I was able to see my unpleasant times with my adoptive father through a completely different perspective, shaped by my life and the knowledge I had gained from life.

Rudy Owens’ memoir on his experience as an adoptee and on the U.S. adoption system.

I described my later life’s wisdom in the introduction to my book, which I published in May 2018: “My adoptive father, a Lutheran minister, was abusive and an alcoholic. He had a serious drinking problem before I was even placed in his and my adoptive family’s middle-class, two-story brick home in metro Detroit. He treated my adoptive mother, my adoptive sister, and me very poorly. At times, when he was drunk, he could have killed my sister and me on more than a dozen occasions—when he would drive us in a total stupor. My adoptive family’s struggles were not pleasant, but they are also things no one could have predicted, and their meaning and purpose may still not even be clear to me. However, the way I confronted these challenges was uniquely my own, and I own how I addressed my reality and the conditions of my life. No one else is responsible for that.”

The Impact of Living through Domestic Violence Never Goes Away

As I continue to reflect on my life, I remain honest that the impacts of my adoptive father’s actions never fully disappeared. I see that most clearly when I read and learn about how domestic violence impacted others in their youth and their eventual journeys in life.

Patrick Stewart in his role as Captain Jean-Luc Picard on the Star Trek: The Next Generation TV series and film franchise.

I only recently learned that the fine British actor Patrick Stewart, known to the world as Captain Jean-Luc Picard of the Star Trek: The Next Generation TV series, also grew up in a home marred by domestic violence. I had always felt something raw when watching Stewart’s performances, as Picard, as Ebenezer Scrooge in his version of A Christmas Carol, and his lesser and earlier roles in films like Excalibur. He always had bursts of rage that felt like a smothering volcano, but controlled just barely.

By accident this month, I found his essay published in November 2009, in The Guardian (Patrick Stewart: the legacy of domestic violence). In it, he laid bare what he and his mother experienced at the rough hands of his World War II hero and domestic-abuser father. He wrote in the bluntest of terms how his father badly beat his mother, especially when he was drunk. He described the terror of living under the shadow of a violent person, who put their lives at risk.

“Violence is a choice a man makes and he alone is responsible for it,” Stewart wrote. “No one came to help. No adult stepped in and took charge. I needed someone else to take over and tell me everything was going to be all right and that it wasn’t my fault. I wanted the anger to go away and, while it stayed, I felt responsible. The sense of guilt and loneliness provoked by domestic violence is tainting—and lasting.”

Everything Stewart described echoed eerily what I had written in 2016, without ever reading Stewart’s essay, penned six years earlier.

In the section of my book I deleted, I wrote: “In those frequent drunken conditions, the ordinary looking man could transform into frightening malevolence, and you never quite knew how he would erupt. The well-worn expression walking on eggshells is actually a perfect match for what my mom, sister, and I faced for years around him.”

I also described the ravaging effects of alcohol, which I internalize to this day, as a survival mechanism. “In those intoxicated moments, my father’s ordinary appearance would be transformed by alcohol. His speech would slur. His left eye would slant behind his glasses. It was the mark an alcoholic I learned to spot instantaneously in others the rest of my life—one of the weird outcomes of growing up around someone with this affliction. To this day I can spot a problem drinkers with Spiderman-like quickness, usually in the first five seconds of meeting them. And my self-defense response kicks into a state of hyper readiness, just in case.”

On some days, like ones I have had this month, I revisit my life’s decisions that still leave sorrow, including my decisions to live a life that eschewed anything resembling domestic normality and middle-class happiness. I still associate these with my adoptive family and father.

Like all of us, we have to confront ourselves and decisions. There are days it is hard, when I might see families that appear “normal,” and I can observe a father who acts compassionately around others without toxic masculinity or the effects of alcohol. On those off days, these apparently normal activities allow me to play “what if” games in my mind.

In the end, I let those thoughts go, because I own this path and my thoughts entirely.

In the chapter I cut from my memoir, I concluded with a meditation on restorative justice. I described how embracing forgiveness means letting go of the power the offense and the offender over a person. It means no longer letting the offender and their actions control you anymore. Without this act of healing, the wound can fester and can control one’s actions indefinitely.

Like Stewart, I cannot entirely let go of the memories of a violent man who failed as a father. But I have found a path to becoming a better person and the person I wanted to be. I never followed in my adoptive father’s footsteps. For that I take credit. I accomplished more than I knew I ever would.