I am re-publishing a story I first published on my website in January 2007. Amid the stories emerging lately about harsh treatment of U.S. citizens and non-citizens entering the United States, I was reminded that any citizen anywhere can be singled out for racist and frightening treatment.

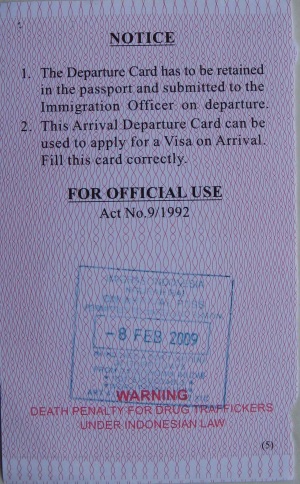

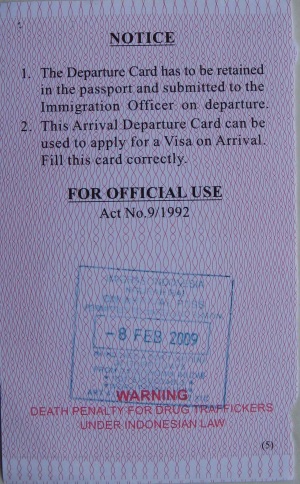

I have been profiled and ransacked entering Canada and the United States several times. Both sides used drug sniffing dogs, suspecting I had to be a drug smuggler. I had a nasty shakedown in Uganda I will never forget. Japanese customs agents did a chemical test on dirt in my luggage, smiling and suggesting it was dope. If it tested false positive (and that would have been a false positive, since I don’t do any drugs), I could have done prison time. Indonesia warns visitors they face the death penalty if they are caught smuggling drugs. I took this warning very seriously and avoided even making eye contact with Bali’s many street dope dealers in the Kuta Beach area. There were rumors many were police informers.

Indonesia makes clear to all visitors if they smuggle drugs, they likely will be killed by federal law.

Here is my experience just before I boarded an Air France flight back to the United States in November 2006, coming from Italy and heading to my home in Anchorage, Alaska. What happened is an accurate record of the events and my efforts to seek an apology from those who treated me as a likely criminal.

When you travel and enter into a no-man’s land at the border, you have no power. No law protects you. You are ultimately at the whim of a state power and the people wearing uniforms. Men like the fictional and corrupt Captain Louis Renault in Casablanca are ready to seize those moments and exert power, for pleasure and profit. Anyone who has traveled knows this. This is universal, not just an issue of one country or one culture.

© 2007, Rudy Owens. All rights reserved.

I am still trying to decide what is worse, French security guards or Disneyland Resort Paris. Both conjure up frightening images. Both overlapped painfully for me when my Air France flight from Rome arrived late at Charles de Gaulle International Airport on Nov. 7, 2006. What followed were some of the worst 24 hours of my life, rivaling my feverish malarial delirium in Africa and the tearing of my anterior cruciate ligament on my left knee for the second time.

When I finally boarded yet another late Air France plane to leave “Old Europe” on Nov. 8, 2006, I had just endured the must humiliating and degrading security shakedown of my life.

Claude Rains as the corrupt Captain Louis Renault in Casablanca. Remember, round up the usual suspects.

Anyone who has gone through this experience knows the feeling that comes when the uniformed power figure mocks the powerless. But the archetypal redneck American sheriff has nothing on the archetypal Frenchman in uniform, captured so brilliantly by Claude Rains as the corrupt French police chief, Capt. Louis Renault, in “Casablanca.” And, like so many ugly archetypes, often a dark, dirty, worm-infested truth lies at its core.

In less than one day, the Republic of France, Air France, and the personnel of Charles de Gaulle International Airport, in Paris, had temporarily turned me into an ardent supporter of the “Boycott France” movement. Though my initial sense of outrage has now passed, the residual sense of fear has not. It is a feeling that I think will always linger when I leave the country, when before I had only known curious excitement.

In truth, I could have forgiven France and Air France for my missed connection at Charles de Gaulle on Nov. 7, 2006, when this all began. I could even have forgiven the accommodations Air France gave me, if I just were allowed to leave France like any other transiting passenger the next day. But no, it was not going to be that easy.

After landing 90 minutes late from Rome, four hours of my life zipped away at Air France’s help desk, where personnel in smart navy blue uniforms speaking smart Parisian French rebooked me on a flight back to the United States the next day and told me I would spend the night at Hotel Cheyenne, courtesy of Air France.

I had no time to ask where this oddly and American-named accommodation was found. I thought, this could be OK; at least I could see a little of Paris, eat some French food, and walk around. I was told, hurry up, the bus was leaving – told in French, of course.

There were about 20 of us international traveling misfits from many countries who were collected on an unmarked bus at 3 p.m. and driven an hour away from de Gaulle, not to the City of Lights, but to Disney’s European bastard child, Disneyland Resort Paris, a.k.a, EuroDisney.

The bus unloaded us at Hotel Cheyenne, a complex adjacent to EuroDisney in the middle of absolutely nowhere. This sprawling corporate complex in the farm fields near WWI battlefields was designed to prey upon European and Japanese affections for American cultural kitsch.

As for Hotel Cheyenne, it was an entirely fake wild Western village, with poorly constructed, two-story wooden hotels named after real and imaginary icons of the old West: Sitting Bull, Wyatt Earp, and Billy the Kid. It resembled a French civic planner’s vision of a Hollywood Western movie set.

A fake western village in EuroDisney in Paris, the prelude to my nasty encounter a day later with Air France private security officials.

The check-in was a chaotic. Our bus arrived minutes after another busload of Japanese tourists. Unlike us stranded Air France passengers, these tourists were actually paying for this experience, rather than enduring it.

I was assigned a room in the Wyatt Earp building, handed meal coupons, and told an Air France shuttle bus would arrive in the morning to take us to the airport.

My room had a faulty heater and smelled of rancid cigarette smoke. I was told by the hotel’s staff I could not change rooms. They were booked full. Full? Who would actually pay to stay here? As it turns out, thousands and thousands of Europeans and Asian tourists do just that.

I walked around the hotel-cum-tourist village. There were fake corrals, fake wells, fake streets, a fake bank, and signs in English to make visitors feel as if they were in Tombstone, Arizona, or a corporation’s vision of what imaginary Tombstone may have looked like. The more I saw, the more I could not believe what was happening. Trapped in a faux Western village, in EuroDisney, miles from any real French town, or even a grocery store, or boulangerie, or anything remotely French.

To kill time, I took a 6 mile run. I did a quick spin first through EuroDisney. It resembled a 1970s-era Six Flags-type theme park in the American Midwest. Fast food restaurants and stores peddled Disney merchandize to mostly European visitors. Large block hotels ringed the amusement area, surrounding a lagoon. I then ran out along a canal to an open space by the road that punched through a farm field to a distant highway. A fog had fallen with darkness. As I headed back to the Wyatt Earp, I followed the grand boulevard, laid out like the entrance to Versailles. Except here the distant palace was that of the Magic Kingdom, shimmering in the mist like a bad dream.

Later that night, the hotel finally posted information that our morning bus would arrive at 7:30 a.m. Because half of the 20 passengers, such as myself, had early morning flights, we would need to book cabs. To our collective shock, we discovered cab fare to the airport was more than 100 Euros, or about $125. We also were told we would have to pick up the tab. This was yet another insult to injury heaped upon us by Air France. I thought conditions could not get worse, but the next day they got much, much worse.

I shared dinner in the fake Western hotel restaurant with Carlo, an Italian designer who, like me, had arrived late on the flight from Rome and missed a connection. Young waiters and cooks and cashiers tended to a crowd of more than 400 visitors. Staff wore cowboy shirts, red handkerchiefs around the necks, blue jeans, and boots. They also spoke French. Most were second-generation Arab and African immigrants. They were super friendly, and I enjoyed our small talk. Mainly, dinner in the fake Western cafeteria had an air of surrealism

Over salad and French wine, I told Carlo our situation was reminiscent of the 1960s TV show called “The Prisoner.” That drama concerned a retired British secret agent sent to a mysterious island prison with a cast of crazy characters, from which he could never escape. Carlo and I laughed repeatedly at our fate and the ridiculousness of our accommodations.

A Long Day Begins, Starting Very Badly at Charles de Gaulle Airport

At 6 a.m. on Nov. 8, 2006, a taxi van arrived. Two Italian citizens who spoke Arabic, the Italian designer, myself, and a fluent-English-speaking Albanian women heading for New York piled into the van before anyone else could commandeer it. We negotiated a fare of 125 Euros. Our driver told us that a French train strike had made Paris’ highways even more congested than normal and that we were wise to be taking our trip now, before rush hour. We arrived at Charles de Gaulle at 7 a.m., in a dark fog. I bid farewell to my Italian colleague, cashed in my remaining Euros at a criminally unfair rate at the airport’s official currency exchange, and made it through customs and security clearance unscathed.

At this time, Charles de Gaulle was undergoing a major overhaul. This repair followed the collapse of part of a new tube-like terminal building that killed four people on May 23, 2004. Because of the airport’s colossal and embarrassing engineering mishap, the airport authority had implemented a complex means of moving passengers to their gates for international flights. Passengers bypassed the terminal walkway and took a bus across the airport to a final waiting area. Here, other passengers from international flights around the world were unloaded, waiting for connections to North America. I was among hundreds on Nov. 8, 2006, waiting to board Air France Flight 084 from Paris to San Francisco, at gate E86.

Charles de Gaulle Airport (creative commons license from Flickr).

Finally, after nearly 24 hours, I could leave this country. After being called by the agents, I and the hundreds of other passengers lined up by the door, from which we would pass through yet another layer of security and walk across the tarmac board the plane. (I later learned these guards in unmarked black uniforms with no insignia nor name badges were private security personnel hired by Air France.)

While standing in line, a young man dressed in a black coat, with no name badge, and sporting a goatee tapped me on the shoulder and indicated I was being pulled aside for secondary screening. He apparently was a security guard, but it was not clear for whom he worked at the time. He never told me who he was, who he worked for, or why I was being questioned.

I sighed, and he took offense. I immediately apologized in my imperfect French, saying, “Excuses-moi, monsieur.” He was extremely offended I made the greatest of all French language errors by using the informal “tu” rather than formal “vous” conjugation. He stopped, pointed at me with his forefinger, and replied, “No, monsieur, excusez-moi,” correcting my conjugation. I knew I was in for trouble.

What followed proved to be the most degrading treatment I have received from any security or quasi-security personnel anywhere in the world. It was more rude than the insulting interview in 1989 by a U.S. immigration official at St. Louis International Airport who likely thought I was a drug smuggler when I returned from nine months overseas; more hostile than the failed shakedown by crooked police officers at the bus station in Kampala, Uganda; more threatening than the hostile lecture I received from a Rwandan military officer after I had tried to take a picture of a tattered Rwandan flag atop a border outpost; and even more demeaning than the over-the-top interrogation, bomb check, triple questioning, and double bag-checking that I received from Israeli security personnel at Ben Gurion International Airport in Israel. This topped them all.

Later I also learned that my 30-minute interrogation occurred just days before a court appearance by former Charles de Gaulle security personnel, most Muslim and of Arab ancestry, who were challenging the airport’s management, known as Aéroports de Paris (ADP). ADP officials had laid off 72 of these workers in 2005. The guard who questioned me was, by all appearances, of Arab ancestry.

I do not know if he was influenced by this touchy labor dispute or if he was taking out his personal, religious, or nationalist beliefs on me. Nor do I know if he was Muslim and perhaps upset by U.S. policies in the Mideast and Afghanistan. Nor do I know if he, as a French citizen, may not have liked U.S. citizens. Nor do I truly know if he had just broken up with his girlfriend, or was a nice guy having a bad day. How could I truly know what was happening in his mind.

I do know that his actions that morning had little to do with any true effort to screen against legitimate security threats or possible criminals. From where I stood, it appeared as if this young guard was carrying out a personal vendetta against a French-speaking – poor French speaking – U.S. citizen just trying to get home. He did a great job in the old human art of humiliation.

That my shakedown had clear racial undertones did not surprise me, given the sharp racism I had repeatedly experienced at a university in France from nonwhite, mostly Arab French residents in 1985. The racial riots that rocked France in November 2005, reportedly in response to France’s deep seated institutional racism against nonwhites, revealed little had changed in France in two decades – racism and resentment were still alive and well in France, among all its residents.

The race riots in France in 2005 that shook the country.

During the questioning and inspection of my belongings and person, I never raised my voice. Not once did I not do what he asked. Not once did I not answer a question, in French. Based on what followed, I have to assume the guard harbored a serious grudge, or just enjoyed the power that comes with a uniform. I treated the guard professionally, calling him “monsieur” and saying “bien sur” when he asked me to empty the contents of my wallet, money pouch, back pack, and suitcase.

When I could not understand some of his French, he threatened me that I would not get on my flight. I took his threat seriously. What’s more, I was not about lose another day of my life waiting for this flight, trapped again at EuroDisney. I apologized that Air France had made me miss my flight the day before and that I was tired and missing work. He merely said, “Calmez vous, monsieur, calmez vous.”

The interrogation proceeded much as if a slave owner would treat a slave, with orders barked for me to obey him like I was a dog. Out came my clothes from my suitcase on the table. Back in they went. My passport was checked twice. Two AAA batteries were confiscated for unknown reasons. He searched, and searched, and searched, but alas, he found no contraband. My medicinal shampoo did raise his eyebrows and curiosity though.

On several occasions, two female security guards gave me eye contact and revealed expressions of shock and disbelief. Numerous French passengers stared at me with similar looks of extreme concern. They did not gaze long as they scuttled out to the plane.

At the end of the screening, the guard also checked every part of my body with a pat down, including twice passing his hands intentionally on my genitalia, which was in view of both other passengers and other security personnel. Never in the United States or in any country I have visited on five continents have security personnel performed such an overt and sexually offensive act on my body in public. I personally believe the guard did this to me intentionally, to humiliate me and demonstrate his temporary and total power over my entire body, in public.

This is an old trick by the powerful over the powerless. It usually gives those in power a thrill, a sense of pleasure, and an adrenaline-type boost, according to social scientists who study such phenomena.

No one stepped in to stop the half-hour-long, fascist-like shakedown. In the end, the guard threatened me yet again, telling me to “calmez vous” once more. I smiled politely back. Before I was allowed to leave, he wrote down my name and passport number and promised me that he would write a report about me. I thanked him and wished him a good day.

Based on my observations, no other passenger allowed on this plane received this degree of screening. Clearly no French citizen received the screening I did – I know, as I was there watching all of the screenings right until I was allowed to leave. I was among the last passengers to board the plane.

I felt that my interests would best be served if I did not ask for this man’s name. So I left without registering a complaint. As I walked on the plane, I turned to the woman walking out with me. We both had endured secondary screenings.

She smiled when I said to her, “That was the most degrading treatment I have ever experienced from a security official. I can’t wait to get the hell out of this country.”

Later, on the flight, I asked the same woman if I had been acting inappropriately. Did I say anything wrong or do anything wrong. The woman, a British citizen and music composer, said, no, you were very respectful. She said it was probably a mistake that I spoke in French. She told me she acted as if she did not speak French, to avoid such problems, though she was fluent in the language. I asked her if I could get her name and contact information. She happily shared those details with me, saying it was important to speak up when security officials behave like the guard who interrogated me.

Later on the same flight, I also got the name of another witness, a public health specialist who worked in Morocco, but was a U.S. citizen. She also received secondary screening, which overlapped during my interrogation. Again, I asked her if I had been out of line, said anything wrong, or did anything inappropriate. She said, no, not to her knowledge. She thought that my faux-pax having “tu toi’d” the guard likely pissed him off. But she added the guard also used lines like “calmez vous, monsieur” with another passenger, a man who didn’t speak French, who couldn’t understand a word of what the guard was saying. It turns out that this other male passenger and myself were the only two men checked by the guard who treated me as if I were a potential drug dealer or international terrorist.

Seeking Restitution–Little Would Come

A few days after returning home, I vowed to do something about the experience I had just endured. In an era of real international terrorism, real terrorism paranoia by national governments, and numerous incidents of security personnel running roughshod over the rights of law-abiding, innocent travelers, I felt I could not let this incident just slip away. Many of my friends and family laughingly encouraged me to let it go. This laughter upset me and encouraged me even more.

I wrote detailed letters explaining my experience to writers and editors at Le Figaro, the New York Times, the Washington Post, the New Yorker, and the Christian Science Monitor. No one at these publications ever contacted me or acknowledged receiving my notes.

Had I been Arab or African-American or Latino and treated in this manner by a U.S. Department of Homeland Security personnel, would the media have cared? I do not know. Perhaps, if I had been handcuffed and escorted off a plane in the United States, it may have been a news story. But because I am white, and this happened in Paris, and I did get on the plane, perhaps my story is just too pedestrian for the interest of busy international news organizations.

I wrote a complaint letter to the Ombudsman for ADP. I explained to the ADP that I had written to the above-mentioned media and to my three members of Congress from Alaska, Sen. Ted Stevens, Sen. Lisa Murkowski, and Rep. Don Young. I explained what had happened to me, described why it was offensive, and demanded an apology. I also copied the French Embassy in Washington, D.C., to attract ADP’s attention. It did.

I received an email within days from Mr. Robert Espérou, the Ombudsmen from ADP. I was informed that I would receive a formal reply, after a preliminary investigation, by ADP. I received that reply on Nov. 29, 2006, from René Brun, Managing Director, Charles de Gaulle Airport.

In his email to me, Mr. Brun wrote, “The check you speak of took place in the boarding lounge and was carried out by a contractor hired by the airline, in accordance with current rules.”

But, no apology was offered in this email. Mr. Brun did offer an explanation, and said that the matter was referred to Air France, as the man in question was not an airport employee. In short, what happened to me was not “his department,” which was the oldest and most reliable bureaucratic explanation ever used.

Mr. Brun’s email also said: “Despite the strict security rules that are mandatory in our country, we share with our airline partners the concern for respecting every person, without discrimination, whatever their origins or nationality. Although every precaution is taken regarding the agents in charge of security operations, unacceptable attitudes still emerge on occasion. I can assure you that we have set up every possible kind of safeguard to avoid this kind of incident.”

In my immediate reply to Mr. Brun, I noted that while I appreciated his response, I thought the email was a whitewash of the harassing and degrading treatment I experienced: “I found it interesting that the private security’s actions were described to be ‘in accordance with current rules.’ Also of note was the statement that ‘we have set up every possible kind of safeguard to avoid this kind of incident.’ Based on my experience, that pledge clearly needs to be realized through better training, better management of third-party security officials, and appropriate discipline when rights of innocent persons are violated.

“I am certain that a private guard instigating a hostile interview because a visitor such as myself speaks imperfect French, threatening visitors such as myself that I would not board an aircraft, and implementing a sexually degrading and humiliating search that including feeling my genitalia twice in public is hardly a professional standard or an example that you are meeting your standards. If these methods are acceptable under your rules, then it confirms my worst fears both about your facility as well as the security mentality filtering top down through French officialdom that is demonstrated against innocent visitors to your country.

“A sad result of your incident is that I, as an American, will never visit your country again, even though I studied there as a college student. A sad result is that I will encourage persons (who earn about $100,000 to $200,000 annually, and who represent the tourist profile you want come to France) to never visit your country because of the security protocols, overt racism, and sexually humiliating interrogations perpetrated by security officials at ports of exit and entry. There are so many other more friendly and inviting countries to visit on your continent. I know. I have visited many of them.”

A second email note to me from Mr. Brun arrived on Dec. 14, 2006. The email said, “I am deeply sorry for the annoyance you experienced at Paris – Charles de Gaulle.”

I felt obliged to inform Mr. Brun later in December that I had also been in communication with Rep. Young’s office twice. I thanked Mr. Brun for his reply and attention.

As it turns out, Rep. Young is one of a group of Republican lawmakers who has repeatedly voiced concern over the original U.S. Patriot Act, though he did not officially register a vote on the legislation in October 2001, in the heat of the post-9/11 lawmaking. He has been critical of the law’s provisions, such as library record snooping.

“I think the Patriot Act was not really thought out,” Young told the AP in 2003. “I’m very concerned that, in our desire for security and our enthusiasm for pursuing supposedly terrorists, that sometimes we might be on the verge of giving up the freedoms which we’re trying to protect.” Young went on to buck his party and vote to limit the scope of the Patriot Act when it came up for renewal, costing him a chairmanship on the Homeland Security Committee in the process. Rep. Young also has been given secondary screenings by U.S. Department of Homeland Security personnel, according to press reports, because his name is apparently on a watch list of suspected travelers.

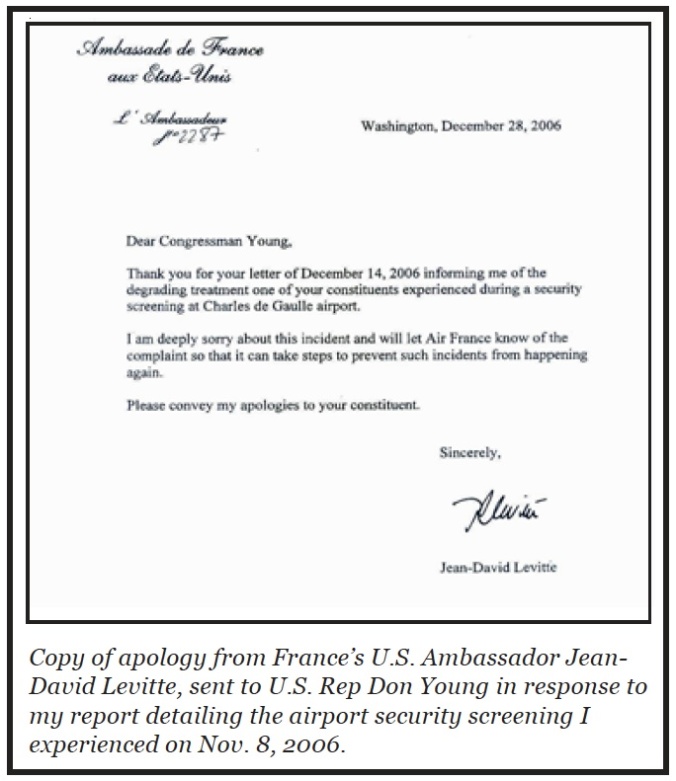

So, perhaps his office felt strongly enough about my six-page documented letter concerning the incident to take action. I was informed by a Dec. 14, 2006 letter from Rep. Young’s office that he had sent a letter to the French Embassy in Washington, D.C., asking for a review and explanation.

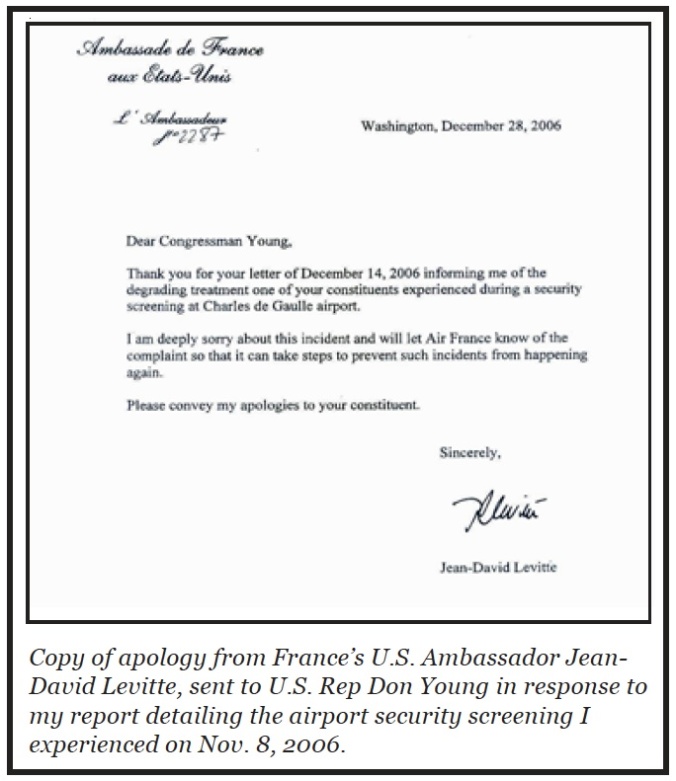

Then, on Jan. 6, 2007, Rep. Young’s office sent me another letter, bringing closure to this little story of one traveler’s encounters with a sanctioned security posture that, as Bogie’s Rick Blaine of “Casablanca” might have noted, “don’t amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world.” The note from Rep. Young’s office shared with me included a copy of the letter sent to him by France’s Ambassador to the United States, Jean-David Levitte, on Dec. 28, 2006. Rep. Young, correctly in my assessment, said, “I realize Ambassador Levitte’s response does not offer much in the way of relief of your experience. I hope a call from the Ambassador’s office will alert the proper officials with Air France to review their screening procedures.”

The note sent to Rep. Young from Ambassador Levitte, which followed my official protests to my member of Congress, was a spare document, less than 100 words and three paragraphs in length. However, it conveyed proper contrition appropriate for diplomatic correspondences for the sender and receiver, including an apology. Ambassador Levitte’s letter referred to my screening as “degrading treatment,” and he noted, “I am deeply sorry about this incident and will let Air France know of the complaint so that it can take steps to prevent such incidents from happening again.”

Ultimately, I do not know if any of my actions will change any policy or prevent private or national guards in France or elsewhere from pulling aside persons, threatening them, feeling them up, and treating them like criminals when they transit through airports. I for one refuse to accept such behavior quietly.

Passivity on a large scale by ordinary citizens is precisely the behavior that feeds the security mindset that can push any country down a fascist slope. I have seen more than 25 old Nazi concentration and death camps in Europe. That is not a state of mind or state of order I ever want to see take shape again, not in my country, not in any country.